Corralling COVID in vulnerable communities

PacMed’s Population Health team uses data and dedication to target testing where it’s most needed

PacMed’s Population Health team uses data and dedication to target testing where it’s most needed

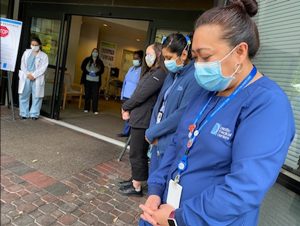

Early in the pandemic, when state and national coordination efforts were still getting underway, one small but mighty PacMed team took our care to the streets. As an arm of a regional collaboration with the Providence and Swedish family of organizations and other county, city, nonprofit and even grassroots and individual partners, PacMed’s efforts were part of many that formed a patchwork of local responses that helped Washington contain the virus early in the COVID-19 outbreak.

In normal times, the PacMed Population Health team crunches data to identify communities and individuals who may need extra care—and reaches out to see how we can help. When COVID-19 first appeared, this team was uniquely positioned to play a critical role on the frontlines.

Tanya Grant, MPH, RN, had moved to Seattle in 2019 to lead PacMed Population Health and Infection Prevention & Control. Before, in Oregon, she led efforts to streamline referrals and sharing of health records between medical clinics and community health partners. Her work draws on personal experience: She has been a nurse for 30 years while raising a special-needs daughter. This firsthand experience showed her “how messed up health care really can be for people—nothing’s easy.”

When health systems don’t talk to each other, patients can fall through the cracks. And during a pandemic, those who are disconnected from testing and care can speed community transmission of the virus. With this in mind, Grant and members of the team—Diana Dass, Abigail Gadia, Hannah Jornacion, Jeremy Viray, Jane Zerabruk, Louela Brown and others—took to the streets.

This was in early June, when protests were erupting nationwide to decry the killing of George Floyd and systemic racism. Knowing that these peaceful gatherings could serve as COVID-19 “super-spreader” events, Grant and her team were introduced by Providence’s President of population health management, Dr. Rhonda Medows, and given permission to set up shop at the epicenter: Seattle’s Capitol Hill Occupied Protest, or CHOP.

“We thought it was really important to be out there in the underserved areas,” says Grant, “to do testing to prevent problems for those communities.” The team strategically located across from the bay of Porta-Potties at Cal Anderson Park and near vital services. They were creative in encouraging people to be tested. “We did trade some snacks for a COVID test on a couple of presumably homeless individuals who were sleeping outside,” admits Grant.

“Everyone was so receptive to getting tested—most people wore masks, and the few that did not, I offered a mask and they accepted it. Also everyone accepted hand sanitizer. This was encouraging,” says Zerabruk, a social worker with the team. “The peaceful atmosphere surprised me.”

Using a computerized system, people were given a number to call for results. People who tested positive were also contacted directly by cell phone. They were given information on how to stay and keep others safe, and referred to King County Public Health, which then conducted contact tracing.

Grant says they tested 450 protesters, along with others who were camped out at the CHOP. “We were able to identify four active infections and prevent other potential community spreads.”

Eventually, “the very last day, it got really sketchy, and the city asked us to move out because they couldn’t guarantee our safety,” says Grant, “so we just moved to the Skyway neighborhood, because we knew that was an underserved population.”

Grant came by this knowledge honestly. The Population Health teams across PacMed, Swedish and Providence use data to understand individual and community risk of disease as the result of many overlapping factors. These factors, known as social determinants of health, include things like race/ethnicity, income, access to transportation, ZIP code and more. “Place matters. Where you live, matters,” says Grant. For example, “we know for diabetes, you’ve got to be able to afford your medicine. You need to be able to afford the good food that we want you to eat. And you have to be able to come into the clinic and be able to monitor your blood sugar appropriately so that you don’t have bad outcomes.”

Based on data they had gathered and analyzed, the Population Health team knew some of the highest risk in King County would be found in the southern ZIP codes, and that “people of color were adversely affected with infections—there are actual disparities that exist. We realized that pretty early on, before even the literature came out about it.”

This knowledge steered the team to their next stop: the Holy Temple Evangelistic Center of Skyway, a Black-led church in a small community tucked between Renton and Tukwila in South King County. They pitched their pop-up tent and set out the “Free COVID Testing” sign. Church leaders got the word out. And because, according to Grant, “there wasn’t a ton of testing in South King County when we when we first went down there,” people came.

Population Health Coordinator Jeremy Viray was struck by people in the area talking about the stress of the pandemic. “Most of the time,” Viray explains, “the folks were really appreciative that we were present and serving their community.”

Even though PacMed’s small Population Health team can only visit each location for a short period of time, those early efforts made an important difference in heading off early potential outbreaks among vulnerable groups.

The nearby Abu-Bakr Islamic Center of WA in Tukwila heard about the PacMed team and requested a visit. While the team could spend only an afternoon there, those hours proved crucial for protecting the community. Grant recounts:

We had about 50 tested—it was in four hours, one Saturday afternoon at the Islamic Center. And two of those were positive. In fact, there wafs one mosque member there who was positive, and she lived in a household of 12 people. We coordinated with King County, and they tested that entire household to make sure there wasn’t additional spread. It turned out another member of the household also ended up testing positive. So, that was a very public health intervention, where we were able to stop an early outbreak.

While Grant’s small team can’t be everywhere at once, their nimble and data-centric approach allows them to get to the best place, at the right time—playing an essential role on Puget Sound’s frontlines against the COVID pandemic, and then connecting with other partners in the response for follow-up.

Their presence in the community is opening even more doors: A Skyway fire chief dropped off his card, saying he wanted to get involved, and the Cambodian community in White Center asked for help with COVID testing at an upcoming event. Grant shares how another community organizer “gave us quite a few leads. So once we’re out in the communities, it’s amazing—to be able to follow up and provide additional services to those underserved locations.”

Grant says the connections being forged by many groups like hers—such as the City of Seattle Navigators, the Reach arm of Evergreen Treatment Services, even grassroots community organizers—are beginning to forge care coordination relationships that will serve us all, in our current public health challenge and in the future. These efforts are organically building an infrastructure that our nation’s health care system has left piecemeal for far too long.

Grant says, “I had the perception, coming from little old Corvallis, Oregon, that Seattle was going to be further along that journey. But it turns out that the problem with care coordination, and collaboration across entities, is the same everywhere.”

However, from her service at the frontlines of the COVID pandemic, she adds, “I was so humbled to meet so many people that were so passionately engaged in caring for that population. At the CHOP, for instance. I was just really humbled to see all the grassroots organization and care for one another that they have there. I mean, there were some challenging individuals… but you know, they all have needs, and we were happy to be there to be able to provide some link to the medical community. Those are the people that I feel like we’re meant to serve: people who don’t necessarily know which way to go. It’s just a real honor to be able to help folks navigate the whole system.

“I think now we can really shift the conversation about social determinants. I think that what happened with George Floyd—his death—really has changed the conversation in a way that I think we’re going to be able to really address race inequity and health care. And it’s going to be exciting work.”

Tanya Grant and the PacMed, Swedish and Providence Population Health teams work behind the scenes to serve our patients and the broader community.