Share what matters

End-of-life wishes and documents are one of the conversations you can have today

See the resources at the end of this article for links to important documents and forms you might need.

COVID-19 reminds us that we don’t know what the future will hold. We may not have the chance to say or do everything we intend to. If there’s anything important to share with loved ones, it’s a good idea not to delay.

For some, this will include sharing sincerely with loved ones what they mean to you. Showing your care also involves letting them know your wishes if you are incapacitated and cannot speak for yourself. This will make a difficult time easier on them, and can give you peace of mind knowing your pets, finances, health care and other matters will be taken care of.

More than a will

Most people know they should prepare a will that outlines their wishes after death. There is another important set of documents for when you are still alive.

These “end-of-life” documents may come into effect if you suffer a coma, seek inpatient treatment for mental health or a substance abuse disorder, or enter hospice near the end of life. Even though you are still alive and in some cases may recover, you could be incapable of communicating or managing your affairs for a period of time.

End-of-life documents do two important things: They make your wishes known, and they empower others to take action according to those wishes. You get to choose a trusted person who will serve on your behalf. This person is then referred to as your “proxy,” your “agent,” or your “attorney-in-fact”—these terms are used interchangeably. You can also identify alternates in case your first choice is unavailable.

Choose someone you trust as your agent

Your agent is someone you trust to speak for you and make decisions on your behalf in two basic areas: health care and finances. After you prepare a document that gives them permission, your agent can be given access to your medical records and other accounts to help them support you. Some people choose the same person as their agent for both health care and finances, while others may choose a different person for each role.

A spouse, an adult child or a close friend can all be good choices to serve as your agent. You should pick someone as your first choice, and also one or more alternates in case your first choice is not available. Keep in mind, your doctor and care team cannot serve as your agent.

Once you have selected your agent and alternates, you should sit down and talk with them. Ask them if they are willing to be your agent, and share what responsibilities they will have and what your wishes are. If you have started a draft of your documents, you can share those. Give them an opportunity to ask questions and take notes. They may bring up things you haven’t thought of.

If you do not know what topics to cover when clarifying your wishes, that’s okay. You can look online or ask your doctor for a document template that will walk you through it.

Put it in writing: Health Care Documents

The first step is to make your health care wishes known. There are many different names for health care end-of-life documents, such as Advanced Directive, Living Will, POLST and Durable Power of Attorney. Don’t worry—you don’t have to fill out all of these! Most of them serve the same purpose.

PacMed recommends starting with the short Advanced Directive form available on our website. This form is only two pages and accomplishes the two most important things: It provides you with simple health care wishes to choose between, and has the legal force to empower the person you chose to serve as your health care agent to act on your behalf.

You can update or add to this with a more complex document if your wishes expand or change in the future. But getting this simple form on file now after a conversation with your agent means you will have immediate support if the unexpected happens.

After you complete any health care document, first sign it in front of a notary or two witnesses. Then make copies and share them with those who need them. Your doctor and your health care agent both need copies of your signed and finalized health care document. Keeping another copy on file at home and even posted on your refrigerator can help emergency personnel if they need to come into your home. You may also want to send a copy to your lawyer and your county assessor’s office for them to have on file.

After the short Advanced Directive is complete, you can always replace this with a more encompassing document, if you wish, such as the long Advance Directive from Providence’s Institute for Human Caring, a Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA) for Health Care, or a medical living will. Resources on these other types of forms are recommended in the sidebar.

Put it in writing: Financial Documents and Digital Assets

After your health care documents are on file, you may also want to think about other things. If you were incapacitated, who would pay your bills, including your rent or mortgage? Who would feed your pets and let your job know?

You need someone you trust to help manage your finances if you are not able. This person will serve as your “Financial Agent.” Their responsibilities could include working with your insurance and accessing any work or state benefits you may be due. If you stop receiving income, they may need to access your savings or liquidate assets to pay for your care. Having someone responsible help with your finances can keep your life in good working, until you may recover and return home.

Some people ask the same person to serve as both their health care agent and their financial agent. Or, if your situation is more complex, you may want to choose one person to manage your health care decisions and a different person to manage your finances.

In order for your financial agent to act on your behalf with your bank, landlord, government agencies and more, you will need a strong legal document, known as a Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA) for Finances. This means the financial agent you choose will have power to act as your attorney-in-fact, another word for agent. “Durable” simply means the document will endure after you become incapacitated.

Banks have been known to refuse some DPOAs, so you might ask your bank if they have a template they recommend. You can also find starting templates online through services like RocketLawyer or LegalZoom, or have an attorney prepare the document for you. Make sure your DPOA is prepared for your state, since each state has different requirements.

Think about digital access when preparing your DPOA. So much of our business is transacted online these days, you will want to give your agent the power to use your online accounts. Make a plan for them to access your logins and passwords. Some ideas are to keep your password list in a safe deposit box, in a file in your home, or sign up for an online password service that provides “digital legacy” or “inheritance” features.

If you choose to have one person serve as your agent for everything—both health care and finances—then you don’t need two separate legal documents. You can prepare one Durable Power of Attorney document that covers both areas. In either case make sure the documents are clear and all your bases are covered. This will help your agent(s), health care providers and others avoid confusion.

Once your Durable Power of Attorney is complete, make it official the same way you did for the health care documents—have them notarized or witnessed, and share copies with your agent(s) and alternates, lawyer, county assessor’s office, and health providers if the DPOA covers health care. Keep a copy for yourself at home and posted on your refrigerator as well.

Final thoughts

When you die, the documents above all expire. To share your wishes about what happens with your money, property and body after your death, you also need to prepare a Will or Trust.

Rather than feeling daunted by the process, remember you can always update these documents later if you change your mind. You don’t have to be perfect.

The most important thing is to get started. Most who go through the process of completing their end-of-life documents find it empowering in the end.

We can feel a burden lifted once we put our wishes down on paper, and enjoy life more knowing things will be taken care of.

Corralling COVID in vulnerable communities

PacMed’s Population Health team uses data and dedication to target testing where it’s most needed

PacMed’s Population Health team uses data and dedication to target testing where it’s most needed

Early in the pandemic, when state and national coordination efforts were still getting underway, one small but mighty PacMed team took our care to the streets. As an arm of a regional collaboration with the Providence and Swedish family of organizations and other county, city, nonprofit and even grassroots and individual partners, PacMed’s efforts were part of many that formed a patchwork of local responses that helped Washington contain the virus early in the COVID-19 outbreak.

In normal times, the PacMed Population Health team crunches data to identify communities and individuals who may need extra care—and reaches out to see how we can help. When COVID-19 first appeared, this team was uniquely positioned to play a critical role on the frontlines.

Tanya Grant, MPH, RN, had moved to Seattle in 2019 to lead PacMed Population Health and Infection Prevention & Control. Before, in Oregon, she led efforts to streamline referrals and sharing of health records between medical clinics and community health partners. Her work draws on personal experience: She has been a nurse for 30 years while raising a special-needs daughter. This firsthand experience showed her “how messed up health care really can be for people—nothing’s easy.”

When health systems don’t talk to each other, patients can fall through the cracks. And during a pandemic, those who are disconnected from testing and care can speed community transmission of the virus. With this in mind, Grant and members of the team—Diana Dass, Abigail Gadia, Hannah Jornacion, Jeremy Viray, Jane Zerabruk, Louela Brown and others—took to the streets.

This was in early June, when protests were erupting nationwide to decry the killing of George Floyd and systemic racism. Knowing that these peaceful gatherings could serve as COVID-19 “super-spreader” events, Grant and her team were introduced by Providence’s President of population health management, Dr. Rhonda Medows, and given permission to set up shop at the epicenter: Seattle’s Capitol Hill Occupied Protest, or CHOP.

“We thought it was really important to be out there in the underserved areas,” says Grant, “to do testing to prevent problems for those communities.” The team strategically located across from the bay of Porta-Potties at Cal Anderson Park and near vital services. They were creative in encouraging people to be tested. “We did trade some snacks for a COVID test on a couple of presumably homeless individuals who were sleeping outside,” admits Grant.

“Everyone was so receptive to getting tested—most people wore masks, and the few that did not, I offered a mask and they accepted it. Also everyone accepted hand sanitizer. This was encouraging,” says Zerabruk, a social worker with the team. “The peaceful atmosphere surprised me.”

Using a computerized system, people were given a number to call for results. People who tested positive were also contacted directly by cell phone. They were given information on how to stay and keep others safe, and referred to King County Public Health, which then conducted contact tracing.

Grant says they tested 450 protesters, along with others who were camped out at the CHOP. “We were able to identify four active infections and prevent other potential community spreads.”

Eventually, “the very last day, it got really sketchy, and the city asked us to move out because they couldn’t guarantee our safety,” says Grant, “so we just moved to the Skyway neighborhood, because we knew that was an underserved population.”

Grant came by this knowledge honestly. The Population Health teams across PacMed, Swedish and Providence use data to understand individual and community risk of disease as the result of many overlapping factors. These factors, known as social determinants of health, include things like race/ethnicity, income, access to transportation, ZIP code and more. “Place matters. Where you live, matters,” says Grant. For example, “we know for diabetes, you’ve got to be able to afford your medicine. You need to be able to afford the good food that we want you to eat. And you have to be able to come into the clinic and be able to monitor your blood sugar appropriately so that you don’t have bad outcomes.”

Based on data they had gathered and analyzed, the Population Health team knew some of the highest risk in King County would be found in the southern ZIP codes, and that “people of color were adversely affected with infections—there are actual disparities that exist. We realized that pretty early on, before even the literature came out about it.”

This knowledge steered the team to their next stop: the Holy Temple Evangelistic Center of Skyway, a Black-led church in a small community tucked between Renton and Tukwila in South King County. They pitched their pop-up tent and set out the “Free COVID Testing” sign. Church leaders got the word out. And because, according to Grant, “there wasn’t a ton of testing in South King County when we when we first went down there,” people came.

Population Health Coordinator Jeremy Viray was struck by people in the area talking about the stress of the pandemic. “Most of the time,” Viray explains, “the folks were really appreciative that we were present and serving their community.”

Even though PacMed’s small Population Health team can only visit each location for a short period of time, those early efforts made an important difference in heading off early potential outbreaks among vulnerable groups.

The nearby Abu-Bakr Islamic Center of WA in Tukwila heard about the PacMed team and requested a visit. While the team could spend only an afternoon there, those hours proved crucial for protecting the community. Grant recounts:

We had about 50 tested—it was in four hours, one Saturday afternoon at the Islamic Center. And two of those were positive. In fact, there wafs one mosque member there who was positive, and she lived in a household of 12 people. We coordinated with King County, and they tested that entire household to make sure there wasn’t additional spread. It turned out another member of the household also ended up testing positive. So, that was a very public health intervention, where we were able to stop an early outbreak.

While Grant’s small team can’t be everywhere at once, their nimble and data-centric approach allows them to get to the best place, at the right time—playing an essential role on Puget Sound’s frontlines against the COVID pandemic, and then connecting with other partners in the response for follow-up.

Their presence in the community is opening even more doors: A Skyway fire chief dropped off his card, saying he wanted to get involved, and the Cambodian community in White Center asked for help with COVID testing at an upcoming event. Grant shares how another community organizer “gave us quite a few leads. So once we’re out in the communities, it’s amazing—to be able to follow up and provide additional services to those underserved locations.”

Grant says the connections being forged by many groups like hers—such as the City of Seattle Navigators, the Reach arm of Evergreen Treatment Services, even grassroots community organizers—are beginning to forge care coordination relationships that will serve us all, in our current public health challenge and in the future. These efforts are organically building an infrastructure that our nation’s health care system has left piecemeal for far too long.

Grant says, “I had the perception, coming from little old Corvallis, Oregon, that Seattle was going to be further along that journey. But it turns out that the problem with care coordination, and collaboration across entities, is the same everywhere.”

However, from her service at the frontlines of the COVID pandemic, she adds, “I was so humbled to meet so many people that were so passionately engaged in caring for that population. At the CHOP, for instance. I was just really humbled to see all the grassroots organization and care for one another that they have there. I mean, there were some challenging individuals… but you know, they all have needs, and we were happy to be there to be able to provide some link to the medical community. Those are the people that I feel like we’re meant to serve: people who don’t necessarily know which way to go. It’s just a real honor to be able to help folks navigate the whole system.

“I think now we can really shift the conversation about social determinants. I think that what happened with George Floyd—his death—really has changed the conversation in a way that I think we’re going to be able to really address race inequity and health care. And it’s going to be exciting work.”

Tanya Grant and the PacMed, Swedish and Providence Population Health teams work behind the scenes to serve our patients and the broader community.

“A huge breath of fresh air”

Sabina Saburova Glaspie struggled to breathe for years—until she found USFHP and PacMed

Over six years and across three military bases on two continents, Sabina Saburova Glaspie—mother of two and a legal assistant for the U.S. Department of Justice—struggled to take in air.

Over six years and across three military bases on two continents, Sabina Saburova Glaspie—mother of two and a legal assistant for the U.S. Department of Justice—struggled to take in air.

After jogging, she says, “I would not be able to breathe.” Others noticed as well. Her husband, friends and even strangers would ask, “Is everything okay, while you’re breathing like that?” “This has been bothering me for so many years,” Sabina says. “Nobody listened to me, that it’s a nose issue. Nothing else.”

Sabina had a sense of what her problem was, but the many doctors she consulted all prescribed the same thing: asthma medications that didn’t help.

That was until her husband, Brandon Glaspie, transferred to serve as a Staff Sergeant at Joint Base Lewis-McChord. The family opted into the US Family Health Plan (USFHP), a TRICARE Prime managed care option for active-duty military families in the Puget Sound area.

This allowed the family to visit the medical team at PacMed.

Sabina started with a virtual consultation, then a visit to PacMed’s Ear, Nose and Throat team (also called otolaryngology). She was nervous at first, due to COVID-19, but “I saw a lady wiping down the elevator button, so that was very, you know, reassuring.”

Her primary care physician, Dr. Alexander Park, referred her to surgeon Dr. Michael Lamperti—all in the same office. Sabina calls her care team “Awesome… very upfront and honest.”

After clearing a COVID-19 test, Sabina’s surgery went smoothly. She had heard that patients bruise up or develop bags under their eyes after similar procedures, but “I didn’t have any of that,” she says. “I had a great experience…. The people around me can’t even tell that I had something.”

Asked what she would tell other patients, Sabina says, “With COVID, I think a lot of people are scared. I know I was…. It was a big, scary moment for me, going to the hospital and under anesthesia for the first time. But the doctors talked me through it, and I had to have some faith in them. In the end, they actually, you know, trained to do this. I should be able to trust them, and I had a great outcome.”

Just a few weeks out from surgery, Sabina is still healing up, but she already feels some relief. “It was, literally, such a relief to get that off my shoulders. Somebody believes me—you actually got listened to. That was very helpful that somebody’s actually paying attention to, you know, to my health, with me, and being a little more proactive.”

Sabina expects even more relief when the swelling goes down. “I can imagine that it would be just a huge breath of fresh air.”

Prepare a home health kit to get more out of virtual visits!

Get the most out of a phone or video visit with your doctor with just a few items. Check your vital signs, give your care team data they need, and even administer basic remedies they might recommend to feel better. Remember extra batteries!

Thermometer. Get a digital model that goes in the mouth—these are more accurate than skin readings.

Thermometer. Get a digital model that goes in the mouth—these are more accurate than skin readings.- Oxygen saturation/pulse monitor/oximeter. You can have alarmingly low oxygen saturation and not feel it! Slip your finger in this small device for a quick reading that can point to respiratory illnesses like COVID-19.

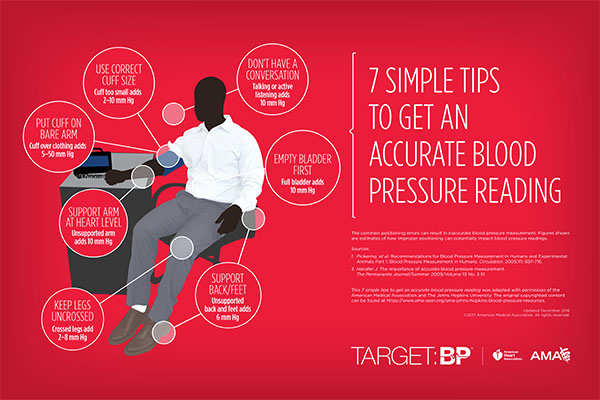

- Blood pressure cuff. Get a cuff for the upper arm with an easy-to-read display. Body posture is important—follow the cuff instructions (more tips online). See below for tips on getting an accurate reading.

- Scale. Keep it basic, nothing fancy needed.

- Tylenol. Unlike ibuprofen or Aleve, Tylenol doesn’t cause GI upset or bleeding, and it’s OK for those 65+. Choose Extra Strength/500 mg. If you are allergic to Tylenol or have liver disease, talk with your provider before taking.

- Nasal rinse. Irrigating the nasal passages helps to relieve congestion. You’ll need a neti pot or a special squeeze bottle, distilled water and a saline mix (find a recipe online).Buy saline packets at drug stores, or make your own solution: 8 ounces of distilled water + 1/4 teaspoon non-iodized salt + 1/4 teaspoon baking soda. If you use tap water, it must be boiled (and then cooled) to prevent infections. Rinse the bottle/neti pot after each use with sterile water and air dry.

Don’t delay! Some of these items may be on back order. Keep these along with your first aid kit to stay healthy from the safety of home. Also, we’d like to share these tips for taking your blood pressure…

7 Simple Tips to Get an Accurate Blood Pressure Reading

USE CORRECT CUFF SIZE

Cuff too small adds 2–10 mm Hg

PUT CUFF ON BARE ARM

Cuff over clothing adds 5–50 mm Hg

DON’T HAVE A CONVERSATION

Talking or active listening adds 10 mm Hg

EMPTY BLADDER FIRST

Full bladder adds 10 mm Hg

SUPPORT BACK/FEET

Unsupported back and feet adds 6 mm Hg

KEEP LEGS UNCROSSED

Crossed legs add 2–8 mm Hg

SUPPORT ARM AT HEART LEVEL

Unsupported arm adds 10 mm Hg

COVID winter exercise: Tips from a Diabetes Star

Terri Woodrow knows a thing or two about self-care while living with diabetes. As one of PacMed’s doctor-nominated “Diabetes Stars,” we had planned to print a story on her approach to healthy living before COVID-19 hit. We were lucky to reconnect with her around her busy schedule, now that she’s back in the (virtual) classroom as a para-educator, to hear how she’s adjusted her health routine for COVID times.

Terri Woodrow knows a thing or two about self-care while living with diabetes. As one of PacMed’s doctor-nominated “Diabetes Stars,” we had planned to print a story on her approach to healthy living before COVID-19 hit. We were lucky to reconnect with her around her busy schedule, now that she’s back in the (virtual) classroom as a para-educator, to hear how she’s adjusted her health routine for COVID times.

When the weather’s nice, get out and about

“I’m fortunate to live close to an urban park area, so when the weather’s nice I’ll go for a 30- or 40-minute walk. It’s always nice to get outside in the fresh air, especially during the winter time.”

Revisit past activities, try new ones

“One love of mine is aerobics. I used to teach it back in the day. I gradually switched from aerobics to running. When I couldn’t run anymore, I tried swimming and other low-impact activities, but was never consistent with them. Recently, I rediscovered aerobics. I found an instructor (Jenny McClendon, a licensed physical therapist) on YouTube. She has a love of teaching seniors and beginners in hopes they know it’s never too late to start an exercise program. It’s perfect for me, now that I’m 65. I’ve also done line dancing a few times a week and resistance training with elastic bands. If it’s something you love, you’re apt to stick with it.”

Find a pace that’s right for you–and keep going

“Along with diabetes I’ve had a few other health issues, like back and shoulder problems, so I’m not able to go all out anymore. I’ve learned through my PacMed doctor and diabetes educator how important regular exercise is to my ongoing health. So, I find the pace that’s right for me and keep rolling.”

Start with the tools you have–but start

“You don’t have to belong to a gym or buy fancy equipment to exercise. Resistance bands are a good, affordable investment. For light weights you can use water bottles filled with dried beans or soup cans. One YouTube video shows you can get in a complete workout just using a chair!”

Mental health affects diabetes, too

“I’ve learned that added stress can cause glucose levels to spike. When COVID-19 hit, and then the riots started, my numbers went up. I’ve learned to limit my news intake, be gentle on myself, stay positive and find things to look forward to. It’s funny, now I get compliments on being so optimistic!

“One thing I’m looking forward to is a three-week driving tour of Yellowstone and the Grand Tetons with a friend. We had to cancel the trip this year because of COVID, but we’re determined to do it next year. I love the planning and anticipation … it’s almost as fun as the actual trip!”

Also read how Terri got started on the path of living a healthy life with diabetes in Traversing the Diabetes Trail.

PacMed is nationally recognized for providing high-quality diabetes care. We help patients manage their diabetes through education, classes and support. Learn more about diabetes care at PacMed.

Let us stand for each other

“Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are.”

– Unknown“Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

– James Baldwin

Fellow Community Members,

We are facing challenging times right now as a society and we need to take a moment to stop and acknowledge the injustices that so many of our colleagues and community members face. Images of the murder of George Floyd have been a haunting reminder of deep-seated injustice that continues to plague our country. There are many underlying causes for this—implicit bias, systemic oppression, a lack of police accountability, gun laws that protect assailants over victims, and persistent anti-black attitudes. For resources on dealing with some of these ills, see below. As understandable frustration spills over on our streets, it can raise uneasy feelings and difficult questions for us: Where do we go from here? How do we support one another going forward?

One of the ways we display our compassion and support for our fellow community members is by speaking up and letting everyone know that the systemic racism that communities of color have experienced in our communities need to end. Although not popular, we need to speak up when we witness these injustices because that is the only way change will occur. We stand with the Floyd family. We stand with Ahmaud Arbery’s family after he was killed jogging in Brunswick, GA. We stand with Breonna Taylor who was killed at the hands of police in Louisville. We stand and expect accountability for the loss of these fellow community members.

At PacMed, we are a community of diverse caregivers committed to providing compassionate, high-quality care to the communities we serve. Part of fulfilling this commitment is supporting everyone, from all walks of life, when they enter our clinic network. We also have a duty to show concern for the misfortunes occurring all around us. Cities across the nation are crying out for change. We support those who are expressing their concerns in peaceful protest. We support better days for everyone. We stand for equality for all and we recognize the need for change in order for every member of our society to feel safe, supported and a sense of belonging.

As we move through these challenging days, know that we all have a voice and we can use it to work for positive change and support those who are unsupported. Now is also a great time to get involved in local government and to find ways to positively influence change so that everyone receives the support they deserve. And let us stand up to individual acts of injustice when we see them in our daily lives, so our neighbors know we have their backs as we together reclaim the space for love, justice, and belonging for all.

Let’s continue to unite and support one another.

Sincerely,

The PacMed Executive Team

PacMed is currently discussing what additional actions we will take to further the work we have done to oppose systemic racism. For now, if you would like to take further action, here are some resources for racial justice and community support:

- NAACP Legal Defense Fund supports racial justice through advocacy, litigation, and education.

- Campaign Zero is a police reform group that has been working on policy solutions informed by data and human rights principles.

TAKE ANTI -RACIST ACTION:

- Learn: blacklivesmatter.com

The official website of the movement that launched the modern fight for freedom, liberation and justice, locally and globally. - Act: kingcountyequitynow.com

Hear from local partners united in a platform to halt predatory development, foster community building and more. - Listen: rainieravenueradio.world

A local, online 24/7 radio station showcasing the diverse voices of South Seattle and those disenfranchised by our rapidly gentrifying region. - Read: southseattleemerald.com

Our homegrown, grassroots online news publication weaving anf equity analysis and perspective into coverage of local issues and beyond. - Bank: blackoutcoalition.org

A compilation on the Bank Black and Buy Black movements, including introductory materials and a map of resources. - Spend: intentionalist.com

Bring consciousness to consumerism by connecting with and supporting the people behind local, small businesses. - Invest: communitypassageways.org

Learn about and support this organization creating alternatives to incarceration for youth and rebuilding communities. - Relate: aapf.org/sayhername

Hear the stories of Black women and girls victimized by racist police violence, and find out what you can do to help. - Connect: bcia-intl.org

Ensure taxpayer-funded organizations are held accountable to goals of bettering the lives of Black families. - Immerse: pinwseattle.org

Grow your understanding of institutional racism through workshops and organizing aligned with others doing similar work in our region and across the U.S.

Spread the news

From frontline to quarantine

It is June 12, 2020. Seattle has entered “Modified Phase 1” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Restaurants are reopening with social distancing, and hair stylists are open for appointments with appropriate screening and masks. It all seems like another planet as I enter the nursing home in Queen Anne to see a new patient. Signs posted on the entry door to the COVID wing direct all incoming providers to observe “Droplet Precautions” with masks, eye protection, gowns and gloves prior to entry. Visitors are allowed to see a resident only at the “end of life.”

The facility is even quieter than usual, and I notice a gathering of all staff in the dining room, just concluding a meeting. There are many staff members I know, and I see some with tears in their eyes as they are coming into the hall. As everyone lines up prior to entry to the COVID wing, they help each other tie their gowns from behind. I mention that this is a “very hard time to work in nursing homes.” One assistant turns to me saying, “I wish that it would all just be over.” Only later do I learn that their meeting was to announce the pending withdrawal of life support for a colleague who has been hospitalized with COVID-19 and on a ventilator.

I could not have imagined this change in the world of nursing homes four months ago. I have worked in nursing homes in the Seattle area for 26 years doing skilled nursing care, palliative care and long-term custodial care. This has always been an environment structured to provide care in a social and family-oriented environment. Facilities have recognized holidays and birthdays with parties. Volunteers come to play music for residents, and pets are brought in to provide love and nurturing. Now families can only come to the window and hold up signs or talk on cell phones to their loved ones.

My entry into this new and strange world was abrupt. I remember vividly my visit on February 26 to the Life Care Center in Kirkland. I first noticed concern on the faces of nurses coming down the hall, reporting fevers on several patients. Influenza tests came back negative. When I got back to my office, I commented to my colleagues that it was very strange to see the cluster of fevers without influenza in the nursing home. Two days later, the patients who had been admitted at Evergreen Hospital tested positive for COVID-19, representing the first-identified outbreak of the pandemic in the United States. Forty-three residents of Life Care died within the next month.

I entered quarantine at home beyond the 14 days required following my visit to the Life Care Center in February. I remained well throughout my quarantine and felt increasingly restless just waiting for the time to pass. I gave up a planned evening of live salsa dancing to which I had purchased tickets. I went on walks and bike rides alone and managed a solo cross-country ski outing on empty trails in the Cascades. It seemed odd and difficult to remain away from family members while I felt fairly confident that the precautions I was taking would protect me from becoming ill. Yet, I also sensed the reluctance of close acquaintances to violate the quarantine. It was indeed a time of being alone.

As I enter the final years of my medical career, writing about my experiences caring for patients has become an increasingly important way to articulate my feelings of loss. Isolation in quarantine represented a reversal in my role; now I was the one being shunned for fear of exposure to illness and contagion.

Seeing things from others’ perspective is an underdeveloped skill in our culture. COVID-19 is bringing my colleagues and me to a new depth of feeling and understanding of the social isolation and loss that patients and their families experience regularly. In a similar way, many across our nation are soul-searching around our collective neglect of the injustices suffered by people of color throughout history, in response to the taken lives of George Floyd and others.

Events of this year have broken us open to see realities we’ve always lived close to, but never dared touch. As we come through this time, my hope is that our newfound openness to the pain of others can help us remain more compassionate and fair to those we love, serve and walk alongside in this world.

Outdoor exercise during COVID-19

Are you confused about getting outside for exercise during this trying time of COVID-19? If so, you’re not alone. Like so much about the current situation, the advice about exercise right now can be confusing.

Are you confused about getting outside for exercise during this trying time of COVID-19? If so, you’re not alone. Like so much about the current situation, the advice about exercise right now can be confusing.

As a sports medicine specialist, I like to think physical activity is an elixir for better health and should be prescribed to most everyone. It’s one of the most effective treatments for multiple health issues (like cardiovascular disease, hypertension, depression, obesity, diabetes and others), and even moderate exercise has been shown to boost the immune system. Exercise is a medical prescription everyone should follow. However, the long-term benefits of exercise need to be pursued while also being smart about the serious risks of exposure to the virus.

As part of our state’s Stay Home, Stay Healthy order, many businesses including gyms are closed. Therefore, exercise needs to be done at home or outside. Yet, many options are unavailable—like parks, beaches and hiking trails that are closed to facilitate social distancing. In addition, the WHO and CDC are now recommending universal wearing of masks when leaving your home, but a mask can make exercise more difficult. All of this information can be hard to sort through.

So how do we exercise—while exercising caution—during the current public health crisis?

Is it safe to exercise outside?

Let’s start with what we know. We know that the virus that causes COVID-19 is spread through droplets released by infected people, such as when they sneeze or cough—and possibly even when talking or breathing. We know these droplets can hang in the air, especially in enclosed spaces. We also know people breathe more deeply during aerobic exercise. A person who is infected may have no symptoms and not know they are contagious. For these reasons, it is of the utmost importance to keep your distance from people you don’t live with—both to protect yourself and to help flatten the curve.

There is also much we do not know yet—but we can apply some common sense. When virus-carrying droplets occur outdoors, it is reasonable to think the concentration will be lower due to the open space. It is possible this would make the “viral dose” you might be exposed to less dangerous. You can lower your risk outdoors even more by maintaining a social distance of greater than 6 feet. One white paper (not yet peer reviewed) recommends staying out of the direct path or lane of people exercising 30-60 feet away, to avoid catching particles in their slipstream.

If you are running, walking or cycling, there is a risk of moving through a coronavirus droplet cloud—however, my assessment is this risk is small overall, so long as you follow the social distancing rules and avoid crowded areas. My recommendation for safety is to maintain a distance greater than 6 feet if you or others are running or cycling outdoors.

Do you need to wear a mask when exercising outside?

If you can use a mask when exercising outdoors, it too would help minimize your overall risk. However, I don’t believe it is absolutely necessary, and it may be difficult to do when exercising heavily. The CDC has information on wearing a cloth mask to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Remember, a cloth or paper mask plays the same role as covering your cough or sneeze: it protects those around you. And since any one of us may be infected with the coronavirus and not have symptoms, wearing a mask when exercising near others can help slow the spread of this disease.

Key takeaways. The risks of exercising outside can be minimized if you follow some guidelines:

- Avoid crowded areas.

- Head outside during slower times. Depending on your area, these may be early morning, during the day when others may be inside working, or in the dinner hour or evening.

- Cover your mouth and nose with a light mask, if feasible, while you exercise.

- For vigorous workouts, try cooler hours, when a mask might be more comfortable (or perhaps unnecessary, if fewer people are out).

- Keep your distance from others. Aim for more than 6 feet if you are walking, running, climbing stairs or cycling, or around others who are pursuing such activities.

- Avoid touching your face during your workout.

- When you return home, take off your gear/clothes and wash your hands thoroughly before touching your face.

- Avoid touching household items (knobs, counters, fridge door, etc.) until you have cleaned your hands.

- If you wear a cloth mask, clean it in a washing machine regularly.

There is risk in life and everyone needs to decide how much they are willing to accept. I think exercise is an important part of life, and while exercising outside has risks, these can be minimized.

I wish you the best in finding ways to maintain your health through exercise, while also taking precautions that make sense.

Chris Maeda, MD, practices sports medicine at Pacific Medical Centers. He sees patients at the PacMed clinics in Beacon Hill, Northgate, Canyon Park (Bothell) and Totem Lake. To schedule an appointment with Dr. Maeda, please call 1.888.472.2633.

Let us know if these tips helped you at StayHealthy@pacmed.org. Read more about PacMed’s response to COVID-19.